A's Minors Midseason Statistical Check-In, Part 5: Offensive Plate Discipline

- Nathaniel Stoltz

- Jul 21, 2022

- 19 min read

We’ve made it to Part 5 of the midseason statistical review of the A’s system, and it’s here that we’re turning to plate discipline metrics. These are often a prime concern of analysts, because they can be conduits to important insights about players’ approaches, which obviously matter a ton as they move up the ladder and face new challenges. Plate discipline metrics also have the advantage–especially relative to a lot of the batted ball stuff we looked through in Parts 3 and 4–of being quite statistically stable. At this point in the 2022 season, we already have pretty good senses of where the various A’s prospects stand on these metrics, so I’ll be doing a lot less of the “small sample, nothing to see here” sort of hand-waving that applied to several of the players in earlier installments.

When we think about “plate discipline,” especially with respect to prospects, most folks tend to content themselves with looking at players’ walk and strikeout rates and then relying on the eye test from there. We’ll start with walk and strikeout rates, and I’ll talk a lot throughout about what my eyes have told me, but we’ll also be diving into some more specific metrics to get additional context on the approaches, strengths, and weaknesses of the minor league players in Oakland’s system. As I’ve been doing, I’ll primarily be looking at the top ten and bottom ten players in each metric that I’ll be discussing, out of a total of 55 eligible players (every prospect-eligible player with at least 85 PA at a full-season affiliate through July 17).

Walk Rate

We’ll begin with the players in the system who have walked most frequently.

It probably shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that the Stockton Ports are well-represented; it’s a lot easier to work walks from Cal League pitchers than the more advanced arms hitters encounter as they move up the chain. Even with that said, Shane McGuire has become my answer to the question “Who has the best approach in the system?,” as he’s incredibly discerning in picking out pitches to hit. The tiny Ricciardi’s standout skill in college was working walks, and it was Rodriguez’s big offensive trait at Vanderbilt as well; both of them manage counts and use their small zones to their advantage. On the other hand, Armenteros, McCann, and Brueser are Three True Outcomes types who swing with more frequency but end up in deep counts because of the rarity of their contact. We’ll see more detail about them later.

Brito and Campos didn’t break camp with a full-season affiliate, and both of them have moved around to a few different levels, but the former highly-touted international duo have gotten on base at solid clips, driven by these walk rates. Campos has shown the superior feel for contact of the two, while Brito has the more patient approach. Finally, Bride and Schuemann are the lone upper-minors representatives: Bride has a McGuire-style surgical approach, while Schuemann is more aggressive and has way more swing-and-miss in his game, but he remains a generally discerning hitter as well.

Conversely, these are the ten players who have walked least frequently.

It might surprise some folks to see the two lists thus far, because the second has more notable names than the first, with four of my top 50 midseason A’s prospects (Angeles, Buelvas, Puason, and Diaz) to three on the walk leaders list (McGuire, Bride, and Schuemann).

There are several different reasons a player might have a low walk rate, and not all of them are bad, though. Angeles, Schofield-Sam, Wright, and Diaz all exhibit a strong feel for contact and can barrel pitches outside the strike zone, which has resulted in their plate judgment lagging behind their contact ability because it hasn’t yet held them (especially Diaz) back from posting strong batting averages. They, like several others on this list (Buelvas, Paulino, and Puason) have been young for their levels and may yet find more discipline as they advance through the minors. Even aside from leading to more walks, and thus higher OBPs than they’ve displayed this year, that sort of improvement will be key for these players to access their power as they advance–all of these younger guys except for Diaz and maybe Paulino have shown in-game power performance that lags behind their raw strength.

The older guys–Eierman, Valenzuela, and McDonald–have not had the same sort of power trouble, as Eierman is near the top of the organizational homer leaderboard, McDonald has a .190 ISO in Lansing, and Valenzuela has suddenly come into some power after his emergency midseason promotion to Midland, hitting four homers in 20 games after having just one in his first 82 minor league contests. Valenzuela is probably the player on this list whose low walk numbers seem flukiest, as he has the lowest swing rate of the ten, but he’s got one of the highest contact rates in the group, and until recently, pitchers had little reason to pitch him with anything other than an ultra-aggressive, zone-heavy approach. He was up at 10% last year in Stockton, so I wouldn’t be surprised to see his walk numbers tick up a bit. Eierman and McDonald are both prone to expanding their strike zones. Eierman’s grooved uppercut swing launches low fastballs but has been of limited utility elsewhere; McDonald has better plate coverage, but he lacks the flexibility to make much out-of-zone contact and has a habit of chasing more waste (i.e., way out of the zone) pitches than most other hitters.

Paulino and Puason have really struggled to nail down consistent approaches, chasing at some of the highest rates in the system, including at waste pitches. Of the two, Puason has the far superior ability to get the bat to out-of-zone locations because his lower half is far more flexible, but their chasing tendencies have put both consistently in bad counts against full-season pitching and given them significant trouble overall. Buelvas has also struggled to post a strong batting average over the past couple of seasons, but he’s been a much better contact hitter and has at least limited his strikeout totals. Still, over two-thirds of pitches against him in Lansing have been strikes, and it’s tough to find pitches to drive when you’re behind in the count that frequently. He’s further along than most of these younger guys in his approach, but still needs to navigate plate appearances with more dexterity.

Strikeout Rate

Now we’ll turn to the other part of the plate discipline coin, strikeout rate. Here are the players in the A’s system with the best strikeout rates this season:

Here’s the flipside of Angeles’, Diaz’s, Schofield-Sam’s, and Wright’s free-swinging approaches: they put the ball in play a ton. Zone control has long been a strength of both Bride–who has taken his miniscule strike rate to the big leagues successfully so far over the past couple of weeks–and Calabuig, who both have excellent histories of getting on base. They swing less than the other players on here, but usually make contact when they do, picking out the right pitches to offer at. Nick Allen is also in the big leagues now, and he also has a high-contact history, though he held his minor league strikeout rate constant while nearly doubling his walk rate this year. He’s under 20% in the big leagues, as well. Foyle is a sleeper outfield prospect with great plate coverage and a good sense of the zone; he’s got more swing-and-miss than Calabuig but makes significantly more power on contact. Maciel, a switch-hitting minor league Rule 5 pick, is more in the free-swinging camp, but like Diaz, he’s made that work so far this year, hitting over .283 in Lansing. Winkler, a 10th-round pick last year, is also posting a league-average offensive statline in High-A in his first full season.

On the flipside, here are the hitters who take the slow walk back to the dugout most frequently.

Again, we’ve got a tendency toward lower-minors guys here; several have struggled to fully adjust to full-season pitching and are still searching for consistency of contact. We’ve already been over Puason’s struggles with chasing bad pitches, and though the similarly-touted Pedro Pineda manages the count much better than Puason does, he’s struggled to make in-zone contact consistently. Since his basic approach is much more sound, I still have a fair bit of confidence we’ll see Pineda improve here with time, and Puason may be making some improvements in the ACL (not included in this sample). Brito has improved his approach and swing path relative to his disastrous stint in Lansing last year, where he was so lost he briefly abandoned switch-hitting, but he still struggles with velocity and keeping the barrel in the hitting zone. Greer has had a more exaggerated version of those issues in Stockton. Brueser has a grooved, low-fastball swing and is limited by his lack of physical flexibility. Armenteros’s helicopter swing is more suited to punishing high heaters, but the complexity of his mechanical operation also limits his ability to adjust to anything else while pulling him frequently off line, but he does have jaw-dropping power when he runs into one. Perez has had a lot of similarities to Armenteros with his extreme rotational approach to hitting, but he’s made some important adjustments over the past month and has seen his strikeout rate plummet since; before then, he was struck in the 37% range for the previous year and a half in Stockton. Since the adjustments he’s made seem directly targeted at improving his ability to move the barrel around, I’m optimistic the reduction since is largely legitimate.

The two upper-minors guys on here, Selman and Fernandez, have both made a lot of hard contact and have bigtime power, but they’re also both uppercut swingers with some holes. Fernandez has some plate coverage but struggles with pitches up in the zone, while Selman has some vertical adjustability but really bails out on offspring stuff away from him.

Walk To Strikeout Ratio

Before we advance to the more specific statistics, I want to take a moment to put the walk and strikeout rates into a bit more context by showing the leaderboards for walk to strikeout ratio and “Two True Outcome” rate (walk rate + strikeout rate). The former is, of course, often used as a loose approximation for the quality of players’ approaches, while the latter gives us a sense of which players’ games revolve the most or least around putting the ball in play. So, first, the players with the best walk to strikeout ratios in the Oakland system:

I won’t comment on these too much since it’s obvious from the previous lists how most of these guys are on here. Bride leads the pack as the only player above 1, and he’s of course been at an even ratio in his brief big league time as well. McGuire and Calabuig stand head and shoulders above everybody else, and both exhibit terrific selectivity and have short, direct swings to the ball. It will be fascinating to see how McGuire handles better pitching, especially since he’s been a low-power guy; he has yet to launch a professional home runs. Harris is a new name here: he excelled in zone control in Lansing, but ran a 24/10 K/BB over his first month-plus in Midland. However, in July he’s back to an even 11/11 ratio there, signaling that he’s maybe adjusting to upper-minors pitching. Harris has exhibited a selective approach at both levels: his biggest remaining hurdle is consistency against breaking stuff.

The players on the other side are all players who have been on a bottom ten list already:

Not much to say to this, other than noting that eight of these players all have strikeout rates north of 30%, but then Buelvas is at a very reasonable 22.3% and Valenzuela just 25% (18.2% since his promotion to Midland!), so those two are in a different category from the others. Angeles manages to avoid the list despite his organization-low walk rate; he’s 11th (.261). Tyler Soderstrom is 12th at .275; he’s struggled with expanding the zone up and away from him.

Walks + Strikeouts

We’ll start here by looking at the players who walk or strike out most frequently. Again, it won’t be much of a surprise, but it puts these performances into a bit of a different context.

So, this list is comprised of two fairly different sets of players: high-strikeout Stockton Ports who are struggling (Brueser, Pineda, Greer, Uhl) and players at higher levels who are having Three True Outcome-style success. Then there’s Perez, who is having success in Stockton since his swing change, but is at just a 40.32% K+BB since implementing it, so his placement on this list has been dropping as his overall line improves, and Brito, who lacks the power of the other non-Ports.

And these are the players whose plate appearances most frequently end with a batted ball:

We’ve got a mix of the patient-but-contact driven Calabuig and Bride and some ultra-aggressive guys. Among the names we haven’t seen much on the previous lists, Winkler and Bautista are a little closer to the Bride/Calabuig end of the selectivity spectrum, while Maciel is a very free swinger. Only Buelvas has a strikeout rate over 20%, and Calabuig, Bautista, and Bride have double-digit walk rates.

With the walk and strikeout rates of the batters thoroughly dissected now, we’ll move on to some statistics that shed light on what underlies them: pitches per plate appearance, strike rate, and swinging strike rate.

Pitches Per Plate Appearance

In the abstract, we tend to apply a loose “the more the better” rule to pitches per plate appearance, right? MLB average is in the 3.9 range, and so we marvel at guys over 4.25 or so and have concerns about those who stay in the mid-3s. Beyond the implication that hitters with Soto-esque selectivity will be seeing and swinging at better pitches, there’s the side benefit that they drive up the pitch counts of the opponents. But at the same time, pitches per plate appearance get driven upward not only by hitters’ patience, but by their inability to convert swings into balls in play. Tim Anderson and Luis Robert are lowest in MLB in this metric by a mile and it works just fine for them. But let’s start with who’s seen the most pitches per plate appearance in the A’s system this year:

There’s a real mix here. Brueser, Armenteros, and Greer all have struck out north of 40% of the time, so a lot of their strength in this metric is a result of their needing to swing several times to put the ball in play. That said, all have a history of patience, and Armenteros in particular was showing a dramatically revamped approach this year relative to 2021, only offering at about 21% of out-of-zone pitches in my pitch charting. Conversely, Butler, McGuire, and Rodriguez are strong bat-to-ball guys with above-average contact rates. Butler swings more than that Stockton catching duo and might come down a bit in a larger sample (he’s at just 117 PA due to a couple of injuries), but he excels at fouling tough two-strike offerings off. McGuire and Rodriguez, again, are on here because they swing infrequently, especially at out-of-zone offerings. The bottom four players on the list strike out over 30% of the time but also show solid plate judgment.

The list of players who have the quickest plate appearances includes some expected names at the top, but also some who might surprise you.

Angeles is right in that Anderson/Robert MLB-leading range, while Schofield-Sam, Maciel, and Diaz’s plate appearances end around as quickly as MLB’s third-leading player in this metric, Austin Hays. All four of them, and Joshwan Wright, who appears a bit further down again, are hit-tool guys whose bat-to-ball acumen has led to a very aggressive approach with swing rates well over 50%. Combine that sort of free swinging with above-average contact rates, and plate appearances come to quick ends.

But this list isn’t just made up of high-contact hitters; it actually has two of the system’s more TTO-oriented guys in Fernandez and Garcia, as well as the fairly patient and TTO-oriented Logan Davidson. Davidson and Garcia seem to like ambushing first-pitch heat, while Fernandez is very aggressive once he gets ahead in the count. Paulino and Richards are also guys with good power who swing a lot: Paulino has a ton of swing-and-miss to his game but swings so frequently that his plate appearances end quite quickly, while Richards also comes up empty with many of his swings but tends to put his contact into fair territory rather than foul, keeping his strikeout rates reasonable and pitches per plate appearance quite low.

Strike Rate

Next, we turn to strike rate. This is a metric that I don’t think gets talked about very much, because we often see balls and strikes as more controlled by the pitcher. But as it turns out, the hitters in the A’s system–or anywhere–can have pretty significant deviations from average in this metric. While it will reflect a lot of the things we’ve already looked at–of course, free swingers will turn balls into strikes more regularly than more patient hitters–it also adds in an element of the pitcher’s perception. Some guys are pitched more carefully than others, so ending up with a low percentage of strikes against you is both a combination of the hitter’s own aptitude for recognizing pitch location and being imposing enough to merit being pitched to carefully. So let’s start by seeing who has excelled, I suppose, at working favorable counts:

The first thing that jumps out to me here is that as we might expect, none of these ten players have above-average swing rates. The 55 eligible hitters for this list have a mean swing rate of 44.9%, and the highest among these ten is Brueser, at 43.1%. The only player in the top 20 who cracks a 45% swing rate is Mariano Riccardi, who is 16th with an even 60% strike rate despite offering at 45.6% of pitches. Yay for having a small strike zone.

There are some smaller guys on this list too, I suppose. Rodriguez and Brito do have small zones, but both are also very patient at the plate. But one thing that seems to also stand out on this list is that the lower-minors players are far more devoid of power than the upper-minors ones. McCann, Harris, Schuemann, and Bride can all slug, and even Calabuig has wielded a fairly dangerous extra-base hit bat this year, whereas McGuire, Rodriguez, Uhl, and Brito are comparatively punchless. Though Brueser has good raw power, he’s also got a 65 wRC+, so it’s safe to say pitchers aren’t exactly pitching around him, either. So the quality strike zone judgment of that latter group of guys is going far at the A-ball level, but it’ll be interesting to watch how that holds up as these players advance.

McCann’s ability to top the list is interesting. He has a massive swing-and-miss problem, always has, and likely always will, but he’s showed a sharp eye at the plate this year. Walks have always been a big part of his game dating back to college–again, if you swing and miss this much, that does inflate the walks in addition to the strikeout totals–but he’s seen the percentage of balls he’s faced climb about three percent relative to his dismal Midland debut last year, putting him more consistently in favorable counts where his powerful swing can find pitches to drive.

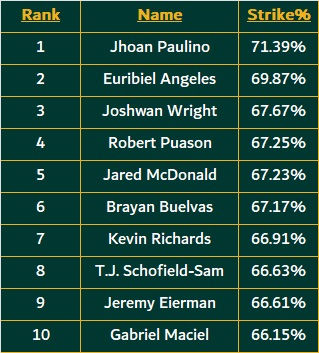

Let’s now turn to the players who have seen the most strikes.

Unsurprisingly, we see the reverse trend here in terms of swinging. Jared McDonald is the most reserved swinger here, at 49.5%, almost five percent above the organizational average. The only players in the top 20 here who swing at below average frequencies are Matt Cross (44.4% swing, 64.46% strike) and Pedro Pineda (41.5% swing, 63.16% strike). All of these top 10 guys have at least a 31% out-of-zone chase rate on my (admittedly incomplete, but reasonably large-sample) pitch charting, as well.

An interesting byproduct of the swing-happy tendencies of these hitters is that, as a group, they actually strike out a touch less frequently than the players who amassed the lowest percentage of strikes. Only Eierman, Richards, and McDonald have gotten to much power this season, with the output of Paulino, Angeles, Puason, and Schofield-Sam trailing behind their raw strength. Some of these hitters–Angeles and Maciel in particular–have managed to make this sort of overaggressive approach work, as Angeles is a bat control wizard and Maciel effectively plays the small ball game, but everyone on this list could stand to get in better counts to do damage more frequently. A notable absence from this list whom you might’ve expected to see is Jordan Diaz, who despite his overall swing-happy ways actually has just a 26.71% chase rate in my data, enough to push him down to 13th here, at 64.41% strikes faced. Perhaps that’s a separator: sure, he swings at an extremely high percentage of strikes, including tough pitches, but he’s relatively disciplined outside the zone, so he has a better chance of getting into good counts than a guy like Angeles by a non-trivial margin. Diaz’s power doesn’t hurt, too.

Swinging Strike Rate

Next, we turn to swinging strike rate. Swinging strikes are, of course, bad. They’re really the only pitch-by-pitch outcome that represents an unequivocal failure on the part of the hitter–he can smartly take a called strike, purposely foul the ball off, etc., but there is no redeeming value in whiffing. Swinging strike rate is, of course, a combination of a hitter’s feel for contact and the swing decisions he makes, so after starting by looking at swinging strike rate, I’ll conclude the piece by examining swing rate and contact rate leaders in the system. First, here are the hitters who have whiffed the least in the A’s system:

Jonah Bride, y’all. And he’s at 4.1% so far with the A’s! Bride ran strong, top-5-type whiff rates in previous seasons, but he’s taken it to a whole new level this year in spite of spending a lot of his developmental time learning to catch on the fly. He’s got a strong batting eye and bigtime plate coverage that allows him to get to offspeed junk away in a way that few righty hitters can. You’ve got mostly a bunch of contact-over-power types below him, with only Harris and Foyle joining Bride as guys with significant punch. It’s really pretty impressive how rarely Maciel and especially Angeles whiff given the extraordinary amount of swings they take. Of this group, only Angeles can’t really be said to be having a good overall season (because he’s had so few walks and extra-base hits), but even his is pretty decent when adjusting for age, again reflecting how tied in with success this metric can be.

The bottom end is a bit less uniform, though.

Unsurprisingly, these are mostly power guys with fairly aggressive approaches, though Greer and Puason haven’t really gotten to their power in games yet. Garcia whiffed at offspeed pitches a full 25.25% of the time in Las Vegas, and he’s going to need to improve significantly in that area to hold down a big league role consistently–for context, that’s a higher rate than Joey Gallo has in the majors this year, and Garcia has done in against Pacific Coast League pitching. Pineda, Brueser, Armenteros, and Greer all have fairly judicious approaches at the plate but have struggled with their in-zone contact abilities. Still, Fernandez, Armenteros, and Garcia were able to post decent overall batting lines despite swinging and missing so much because of their ability to do damage on contact.

Swing Rate

The rate that batters swing is central to a lot of the statistics we’ve reviewed here. Unlike all of them, it’s not a statistic that’s easy to find for minor league baseball players–none of the major statistical sites list it (beyond the publicly-available PCL data, that is). That doesn’t mean it can’t be derived from minor league Gamedays and what not, but that takes scraping talent, which I don’t have.

Thankfully, the person behind the great Down on the Farm newsletter–which has all kinds of fascinating information on the minor leagues, including where the A’s rank in a number of organizational metrics–does have that talent, and he graciously shared the data with me. Thus, we’ve got a more complete picture here than what my partial charting data–which comes with, for instance, the bias of having entirely road games for Stockton–would be able to provide. So behold! Here are the A’s minor leaguers who swing the most frequently!

It’s worth saying that for a majority of these guys, this sort of approach makes some degree of sense. I’ve talked about the hit-tool prowess of Angeles, Maciel, Diaz, and Wright already, but Schofield-Sam and yes, even Robert Puason also have good lower-half flexibility and an ability to adjust the barrel. As bad as Puason’s swing decisions often have been these last two seasons, he will occasionally barrel something a good deal out of the zone. Not to the extent you see it from Angeles, Diaz, and Wright, but one can understand where the impulse comes from. Even Richards and Selman have reasonable barrel adjustability. It’s really just Paulino who is completely ill-suited for this approach: his uppercut features big leverage and strength from his hands, but he hasn’t shown much ability to adjust its path.

On the other hand, here are the system’s most judicious swingers.

We’ve seen a lot of these guys on some of the previous best-of lists: this seems to follow Eno Sarris’ work on how good not swinging is. That still has its limits: it hasn’t propelled Uhl, a defense-first backstop with limited bat speed, to a stellar offensive season in Stockton, nor has it saved Brito from his near-40% strikeout rate. But even they–as with the other names on the list–do walk a lot, and the other six names in the top eight benefit further from this approach by making consistent contact. Denzel Clarke’s Stockton breakout–where he appeared a lot less raw than expected when he was drafted last season–was largely fueled by the quality of his approach: again, even as he missed on a third of his swings, he was putting himself consistently in good counts that maximized the likelihood of getting pitches to hit.

It’s worth emphasizing that some of the names on this list are more surprising than others–swing rate does reflect hitters’ instincts, but swinging is a choice, and hitters can change their choices as they develop. Down on the Farm provided me with this chart of the biggest changes in the A’s system swing rate from 2021 to 2022.

So the change to uber-aggression is indeed a new one for Wright; though he has the contact skills to hang in with this approach, his extra-small strike zone may be a good reason to possibly dial back toward the 2021 number. Selman also notably controlled the zone much better in Lansing last year than he has so far in Midland. He’s struggled with chasing breaking stuff down and away. Buelvas’ aggressive turn has been less visually apparent to me than those of the two players ahead of him–perhaps because he wasn’t around as long before getting hurt–but it’s also landed him in comparative statistical trouble. Butler’s, Davidson’s, and Perez’s changes have been more welcome, as they all got overly passive at times last year and would end up swinging at a preponderance of two-strike offerings after letting hittable pitches go by.

The players who have reduced their swing rates have generally been met with equal or increased success this season relative to 2021, again supportive of the idea that not swinging is good. I’ve talked about Beck’s adjustments at considerable length before, and this number sheds particularly pointed light on them, but it’s Bechina who has dialed the swings back the most, adjusting to the upper minors after being rushed there last season. It’s worth noting that the games of seemingly-polished hitters like Calabuig, Allen, Machin, and Schuemann continue to evolve, and there’s McCann again: it’s not a huge chance, but it may be an important part of his turnaround this year.

Contact Rate

From the swing rate data and swinging strike rate data, we can derive the rates at which each of the A’s prospects makes contact when they swing. Here are the organizational leaders:

There’s Bride leading the way again, as you’d expect with his whiff rate dominance, but you’ve also got Harris and Campos showing the well-roundedness of their hitting ability here, as they’ve also employed sound approaches that have enabled these contact rates and resulted in career years. Calabuig and Mondou are longtime masters of the contact craft, and McGuire is establishing himself as one in his first pro season. Given the frequency with which Maciel, Diaz, and especially Angeles offer at tough pitches, their ability to hit them–often with some force–at this rate is a testament to their hand-eye coordination and plate coverage. That doesn’t mean things wouldn’t improve some if they could cut their swing rates to the 50% range or a touch below, but as we see in the flipside of this list, it’s proof that making contact isn’t all that contingent on pitch selection by itself.

Again, a major theme of this group is rawness, as over half of these guys are Ports. Uhl and Brito are up here despite their very patient approaches, and actually all of the top five hitters here are reasonably disciplined at the plate, as is McCann with his organization-low strike rate. I guess to some extent, that makes sense: it’s kind of the inverse of the plus-hit/chase phenomenon with guys like Angeles and Diaz, even though it’s striking at first glance that the hitters who struggle the most to make contact are generally swinging at a better selection of pitches to hit. But then there’s Paulino, again reaffirming that he’d be much better off going to a take-and-rake kind of approach, if he can. The same might go for Fernandez, the only other aggressive hitter here, but it’s working for him with his absurd line-drive ability and plus power. I do think there’s significant upside for Pineda to improve here, just as we’ve seen with Perez over recent weeks. As a cold-weather high-school draftee still early in his career, there may yet be some growth for Greer as well: he made progress in Rookie ball last season.

That’s it for Part 5. In Part 6 next week, I’ll go through these sorts of stats for the various pitchers in the A’s system.

Comments